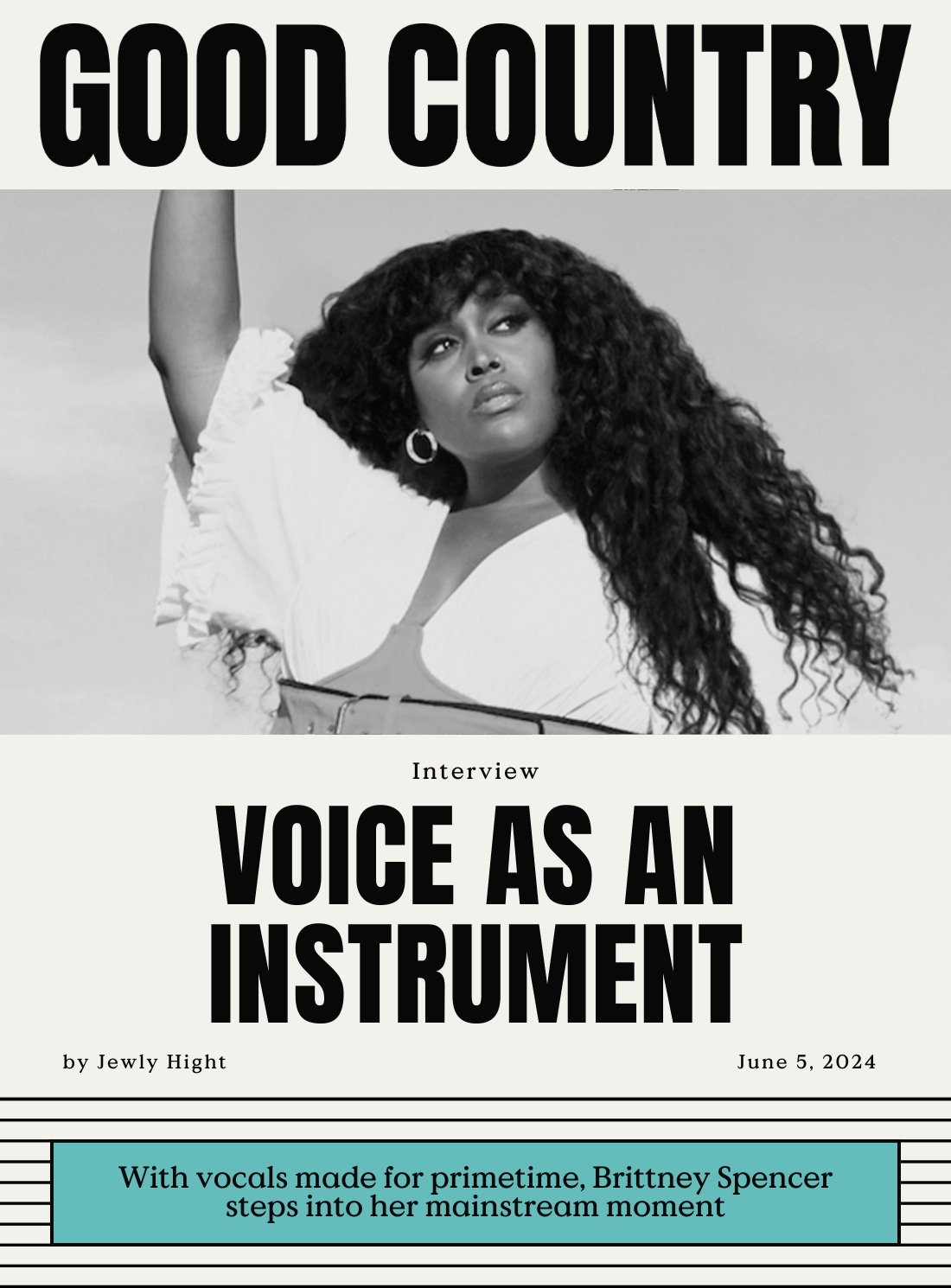

Voice As An Instrument

With vocals made for primetime, Brittney Spencer steps into her mainstream moment.

The most remarkable thing about the way that Brittney Spencer sings on her debut album, My Stupid Life, is her casual display of versatility. Across a dozen tracks, it’s evident that she has options when it comes to how she’ll use her voice.

During “I Got Time,” a breezy invitation to shared, summery pleasure, she shows her down-home side with sly, bluesy dips, and when she summons angst over romantic risk in “Desperate,” her sumptuous inflections soften the edge of '90s-style country twang. She builds up to the pinnacle moments of “Bigger Than the Song” and “Deeper” with well-paced phrasing and a feel for just when to deploy intimate, husky sighs, rippling, country curlicues, and molten R&B runs.

Through it all, Spencer never sounds like she’s reaching, redlining, or laying it on too thick. And yet, throughout her first big promotion cycle this year – and the profile boost she received from her Cowboy Carter credit – the Baltimore native has gotten little attention for the discernment she shows in her country-pop singing. Good Country waded in with her.

Jewly Hight: When people ask you to recount the pivotal moment when you got into country music, usually it begins and ends with someone recommending that you listen to the Chicks, and you taking the recommendation. But I want to know, what did you hear in that music? What did you hear in Natalie Maines’ singing that grabbed your ear?

Brittney Spencer: For me, it felt like something familiar, but also new at the same time. I think there are a lot of commonalities between country music and the music that I heard growing up in church.

It was the harmonies. In Black church, we have quartets. I mean, I guess [they’re] in any church, maybe, but quartets are a huge part of Black church. And I grew up singing in groups. I learned how to sing because I sang with people. That was my introduction. I learned to sing because I listened to other people. I harmonized with them. We heard each other. We blended together. And I think a lot of how I view the world, maybe it stems from that.

When I heard country music, I heard the commonalities first before I heard the things that made it so different from the world that I was accustomed to. And then I heard like songs like “Sin Wagon,” come on, man. There's no way you can tell me that bluegrass and country and gospel don't have very, very similar traits at times and I just thought it was really cool musically to hear them.

I always connected to music. But it was the storytelling, the way that they crafted lyrics that made me kind of start to pay attention to words a lot more. I know that there are a lot of genres where people can tell stories; country music doesn't have a monopoly on that, you know, but it's the genre where I started to understand storytelling.

I looked to see if I could find old footage of you singing in a church setting, in an ensemble, in a choir, something like that, and couldn’t find any. So, can you take me back? In church groups, what part were you singing and with what kind of vocal attack?

Gospel music is so vast. It's probably why my album sounds the way that it does. We can be singing a song that is very down-home church and then you have something that's more contemporary. They can have a song that is with the choir and you can have a song that sounds like it's more of a praise and worship-y thing.

The thing about gospel music is that it's like, “Get in where you fit in.” In church, I didn't want to sing soprano, but we always had too few. No one wants to sing soprano. I can get up there, but I don't want to live up there. I just want to have visitation rights, you know?

Growing up, I’d have to sing whatever was there. I wanted to be an alto. I sang with groups a lot. We would be on the phone just harmonizing with each other. That was what we did for hours. We didn't have singing lessons. And then when we finally got to church and got to sing, we'd spend as much time as we could doing things acapella, showing each other songs that we just heard and exploring stuff together. I was doing all of that while also singing classical music all throughout middle high school and community college and doing opera competitions.

I read that you auditioned for the Carver Center, your performance arts school, with an Italian aria and a Broadway tune. What kind of training did you get there and how did you explore just other sides of what your voice was capable of?

In order to get into the high school, I had to sing an Italian aria and I had to sing “In My Own Little Corner” from Cinderella. Those are two very different styles. Even in the ninth grade, the first quarter we were singing in Italian, the second quarter we sang in German, the third quarter we sang French.

There's range, and I think in country music, there's range as well, but I bring that with me, because I'm still that girl who had to audition in high school with an Italian Aria and with a Broadway song. I know that there are differences in styles and genres. I just came up in a tradition where you learn how to do it all. So for me, picking country music is really a heart thing, coming from the background that I have, it's a special thing when the person who can do a whole lot of things chooses the thing that they feel drawn to.

I think a lot of people are probably hearing you for the first time this year because of your album and because of you being on Cowboy Carter. But this is a longer journey of artistic development and self discovery that we're talking about. What other kinds of singing experience would you point to that you felt were important to your development?

Singing with my friends. House shows. Songwriting camps that I've done through the years.

I don't mind the industry. I do consider myself a commercial artist, and I want to be commercial and marketable in that way. I want to reach as many people as I can. But I don't want to do it at the expense of, of feeling intimately connected to people

People often speak of country singing as though that means one thing, one style of singing, but that's never been the case. There are so many different traditions and lineages and styles and approaches to it. One simplistic way to divide it up is the countrypolitan or country-pop side that’s more open to outside, popular influences and the harder edged, down-home side, that has rural connotations. What kind of country singer did you set out to be?

When I first started having a moment back in 2020 and labels wanted to talk, they would ask me, “What are you patterning your sound after?” And I remember trying to find a way to explain, “I’m, like, universal country music. What if Adele was a country artist?” I'm definitely not the first to do what I'm doing, in terms of wanting to make music that blends a lot of things together, but it's still rooted in country music. So it's not that I'm trying to make some sort of sonic space [just] for myself, but I'm trying to be real about it.

In the time that you have been in Nashville, I've heard so many different examples of country acts drawing in elements of pop or hip-hop or R&B, in vocal approaches as well as in production. But that doesn't mean that everyone who's attempted it has pulled it off. I've heard many examples where I can hear how calculated and strained it sounds. But you do it with low-key ease on My Stupid Life, incorporating pop or pop-R&B vocal flourishes in a way that never sounds forced, never sounds showy. It made me wonder whether you had reference points for where you wanted to take your singing.

I like to leave people wanting more. And also, whatever I sing needs to serve the lyric. I believe the lyric and the melody both are equally important.

It took a while for me to even develop my sound. What does a girl from Baltimore City singing country even sound like? But the thing that I go back to all the time is, “Just sing and be yourself and also listen to the lyric.” The lyric would tell me how to sing. It was the attention to lyrical detail that made me feel like I was starting to understand my own artistic voice.

I saw you open for Grace Potter at the Ryman a couple months ago, and it gave me new perspective on the way that you use understatement. You have a rich, robust vocal instrument. I got the impression that you could, at any moment that you cared to, really unleash and go explosive, but you were using that power selectively.

I feel those more vulnerable songs, sometimes I'm not screaming them because it's not easy for me to even talk about being vulnerable. I don't need to be screaming and yelling. There's a place for all of that. And it might not be a whole lot of runs in those songs. Maybe I'm feeling timid. I probably am being vulnerable.

There's this grand tradition in country music of shouting out predecessors and elders and icons and showing that you're in that lineage by naming them. And in “Bigger Than the Song,” you reel off familiar names, Aretha, Reba and so on. There’s only one artist you mention who’s actually a contemporary of yours, Maren Morris. She also moved between pop, R&B, and country with fluency on her first Nashville album. What did you mean to say by including her?

I think of her as one of them. When you become friends with someone that you have been a fan of for so long, it just makes you feel so dorky. But I do geek out over Mickey [Guyton] and Maren all the time, because I love them. And even though we're close friends, I still hold them in such high artistic [regard]. I put Maren in it because her Hero album talked me off the ledge. I was seriously like, “I don't know if I want to do this anymore.” I could hear all of her music influences when she was singing her songs. It made me feel like, “Man, she's having a huge moment with this. Maybe one day Nashville will be ready for somebody like me.”

Beyoncé is another name in the pantheon of singing icons you laid out in that song. I saw your streaming numbers spike with your feature on Cowboy Carter. How have you actually experienced the impact of being on that album, having your name in those liner notes?

Being part of this Beyoncé record has done so much for me as a new artist, both personally and artistically. It's kind of wild to watch [another artist] be able to have that kind of power, you know? I've experienced it a few times in my career, and this is definitely the pinnacle of it, ‘cause it's the biggest artist in the world.

Her bringing us on, it was definitely a heartful choice of engagement. 'Cause Beyoncé don't need nobody to sing with her. She's doing what she wants to do. She collab-ed with our country legends. She collab-ed with some of the biggest names in pop. And she decided to engage with new, Black country artists. This album was going to be number one with or without a Brittney Spencer. I think a lot of this is a testament to who she is, as a person and as an artist. She keeps her ears to the streets, man.

Since you’ve spent time with Cowboy Carter has the expansiveness, experimentation and eclecticism, reference points from all over the place, sparked any ideas for you?

If you're working with country reference points, I feel like I heard that in Lemonade. I feel like I heard that in songs like “Daddy's Lessons.” It didn't start with Cowboy Carter, in terms of inspiring me to explore with sound and production. I mean, her performance on this record is insane to me. There are choices that she makes with her voice. It's not just like, “Hey, I can sing.” She is giving theater.

She's just kind of furthered me down the rabbit hole of inspiration. I might need another lifetime to try and sort through her archive of genius. That, for me, is a personal treat. I know this album is for the world, but as a fan and listener, I am like, “You brought all of that brilliance down my back road.”

I think she's teaching a whole generation of people how to approach artistry with no limits, and to let your voice do what it can do. And to not be boxed in by institutions or any sort of industry rebuttal or pushback. Because if it's in your heart to do and if you can sing your ass off, sing your ass off.

Lead Image: Brittney Spencer by Jimmy Fontaine.