Hand To The Plow

With their new album, Lawrence Rothman digs into thorny topics and finds redemption.

Artists often lightheartedly describe songwriting as their preferred form of therapy, but for some – like genre-shifting Americana chameleon Lawrence Rothman, the mental-health benefits are no joking matter.

With their April-released solo album The Plow That Broke the Plains, the Missouri-raised singer-songwriter put in some serious internal work, deconstructing deep, devastating themes for a project that hits like a ton of bricks. Topics like addiction, societal pressures, and self-worth are all explored – plus their survival of a literal attempted murder over gender expression and a near-fatal battle with body image, as Rothman heals old wounds they once just papered over.

Centered on their bold, riveting voice and featuring a powerful sonic blend of country, indie rock, and alt-pop, these tunes are as raw as it gets, coming with built-in support from guests like Amanda Shires, Jason Isbell, and S.G. Goodman. Because, as Rothman found out, fighting for yourself doesn’t mean fighting alone.

Chris Parton: Tell me what you're feeling now that The Plow That Broke the Plains is out. I know you put a lot into it, so now that people can hear the message, how does it feel?

Lawrence Rothman: I got to say, it feels really good to close a chapter of my life. I'm very much into documenting periods of time within my life through art and through music. And for me, it's sometimes better than an actual counselor or psychologist. Having the art to vent through and then release it out into the fire of the world and let it burn, I feel cathartic every time I do it.

What was that chapter about for you?

It was post-COVID when I wrote the record. The world had just been getting semi-back to normal, but none of us can deny what the isolation of COVID and the strangeness of it did to the world and to everybody's head. It affected everybody in their own unique way, and I was emerging out of that period like, “I'm free again. I can go to places, I can live life again.” But I think I went too far as far as having a good time, or just things that are more destructive than constructive.

You're dealing with some really heavy themes – whether that’s personal or societal. Were they all connected for you?

Yeah, definitely. I'm sort of a sponge to the outside world, so if I'm out and about too much, I soak everything up and for good or for bad, and I'm definitely an observer type. I like to watch and listen and see what other folks are doing or where their heads are at. And I write about that a lot. … Sometimes if you soak up too much of the energy of the outside world by observing, it can kind of get to your head as well.

I read that the album started after you had to go to the ER in Nashville, right? Would you be open to explaining why?

I mean, it's one of those things I'm not proud of and it's hard to talk about, but truthfully, social media paints pictures of people's lives or the way people look in a way that no matter how strong you are … it can kind of beat you down a little bit. I found myself doing a lot of extreme dieting and weight loss pills, but at the same time, I'd balance it out by getting exercise and trying to eat healthy, but it was an almost lethal and deadly sort of tight rope that I was walking. …

I got in a very, very dangerous spot where I was taking too much weight loss pills and doing laxatives and weight loss teas, and my stomach and my insides started to collapse. I ended up in the ER with internal bleeding, and I'm very cold turkey about things that are addictive, so I got on the plane home [to Los Angeles], I wrote one of the songs on the record, "LAX," which was a play on laxative.

Oh, wow. I didn't realize that – I thought it was just the airport code.

I landed and did two weeks of self-reflection and talking with the people I love, just trying to figure out how to change my train of thought. And so far, I'm knocking on wood right now. So far I haven't gone back to any of that stuff. I mean, it's like a drug addiction, very much like a drug addiction.

Tell me about "Poster Child." This is a really striking song about how you were shot just for existing, basically. Can you explain where that came from?

In my young-adult band, we were playing a concert in Dallas and I got on stage, and was dressed for – well I guess for some of these audience members, not in a way that they liked. I had makeup on, and a mix of what I guess would be known as something a woman would wear.

I dunno, to me, it was a rock ‘n’ roll look. It was fun, and I was just being myself. But I got off the stage and I was backstage maybe eight minutes when three guys jumped me and broke my ribs and shot at me. It was very traumatic and also a turning point in my life, just realizing that people can go to great lengths if they don't approve of who you are. Somebody could kill you. And I knew that existed in the world – that kind of evil. But I never experienced that myself.

It was eye opening. I was definitely scared to perform for a while, and to this day, I sometimes have a little bit of a trigger with performing. So when I hooked up with Jason [Isbell] to do some writing for this record, I walked into Jason's barn studio, and he was like, “All right, what are we going to write about?” We start talking about that story off the cuff and I didn't plan on writing about that, but he's like, “Well, that's our song. Let's go.” So we wrote it really quickly with two guitars in about an hour and a half. And that session with him, that little moment we had, I fell back in love with the guitar again.

Your lyrics there keep coming back to this phrase, "Can we use that?" It seems like there's some conflict in there.

It's one of those things as an artist, when you put out records, there's always got to be some sort of hook or story about what the record's about, and I'd never really wanted to draw any attention to that situation that happened to me. I remember when it did happen, I was on a big record company at the time, and they were trying to exploit the hell out of the fact that that happened to me. I wouldn't do any interviews. I wouldn't even talk about it. I always just stayed away from it. But it being so many years later – and with the state of where the United States is, the temperament of the U.S. right now – it felt like now is the best time to talk about that.

Do you feel like doing the record was important to help you work through this stuff?

Yeah, I mean music has always been my therapy, but this particular moment in time when I made this record, a lot of the songs were written in early 2023, late 2022. During that little period, I really needed that music therapy and it healed a lot of wounds. It closed a lot of chapters. Standing here today, honestly I have to say there was a period of time with the weight loss problems and bleeding stomach, and just my whole mental condition, that I didn't think I would be talking to you right now. I really felt like I was definitely lost, but that period's long behind me, and I know that the record was 80% of what brought me out of the dark, dark cave I was in.

What do you hope other people take away from this?

With this type of album, I think there is a relatable thread for everybody in all walks of life, which is that you're stronger than your demons at all times. And demons are just demons. They're not immortal and they can be killed and destroyed. When you find yourself falling down into the portals of hell, slay your demons and you can climb back out. And there's going to be a better spot for you in the world after the fact.

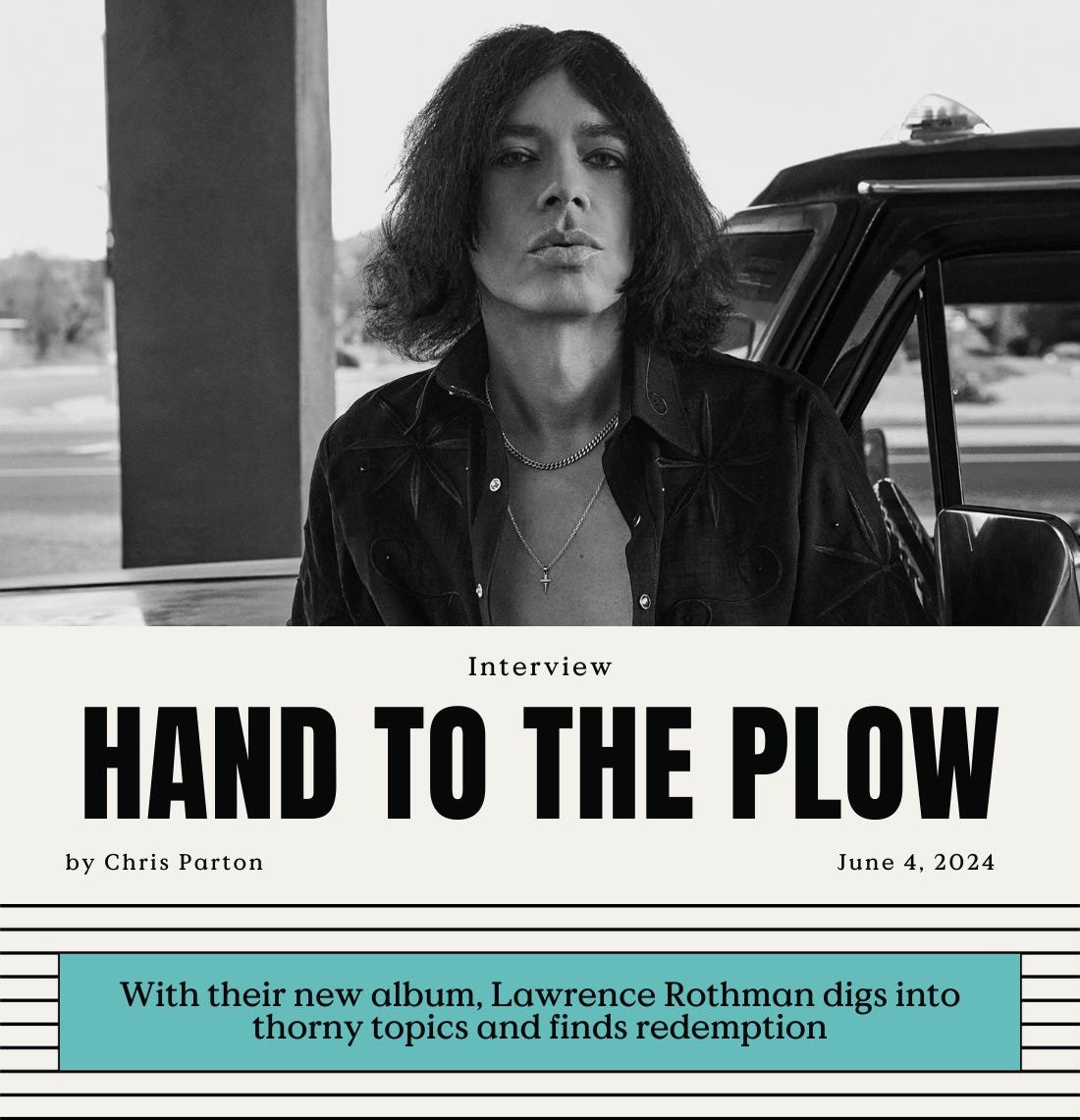

Photo Credit: Lawrence Rothman by Mary Rozzi.