Genre Boundaries Blurred

Tenille Townes is a compelling example of an artist charting her own course.

“Genres are a funny little concept, aren't they?” Linda Martell poses rhetorically during the spoken intro to “Spaghettii,” roughly halfway through Beyoncé’s western epic Cowboy Carter.

“In theory,” Martell goes on with sly poise, “they have a simple definition that's easy to understand. But in practice, well, some may feel confined.” Martell knows what she’s talked about. She endured all manner of efforts to hem in her musical sensibilities and diminish her agency back when she was country music’s most visible Black, female talent.

And now, because she lent her voice to a track where Bey and Shaboozey go hard with downhome boasts over a lurching beat, she’s up for a GRAMMY for Best Melodic Rap Performance. Other tracks from Cowboy Carter are in pop, country and even Americana contention, a staggering range of styles for one project to cover.

That’s the kind of boundary-blurring year it’s been, with Shaboozey translating country gestures and imagery to broody, contemporary hip-hop cadences with tremendous savvy and both Jelly Roll and Post Malone furthering their paths from rap origins to ever more fully embracing – and being embraced by – the country music industry.

Things haven’t been any tidier on the rootsy side of the spectrum. After being treated like a pop prodigal during her Star-Crossed era, Kacey Musgraves’ shimmering, urban folk revival-echoing ruminations on Deeper Well have been received as a country homecoming of sorts. Noah Kahan has helped bring on a resurgence of cozily folk-forward, singer-songwriter sensibilities in pop music.

A major country record label snatched up the Red Clay Strays, the type of crowd-pleasing, Southern blues-rockers that have long been celebrated in the Americana scene, where many other pivotal voices – first Allison Russell last year, then Sarah Jarosz, Amythyst Kiah, Adeem the Artist, Kaia Kater and others – experimented with lusher or more polished arrangements and production aesthetics in their latest work.

Tenille Townes offers us a particularly compelling example of an artist charting her course against the background of that extreme slippage between genre lineage, stylistic markers, and industry affiliation. She tried the major label country route in 2018, greeted as a promising new voice at a moment when the broad appeal of Kacey Musgraves' Golden Hour ruminations made the industry a little more receptive to artists with a personalized, writerly bent, and she's emerged independent on the other side. In her mind, being unfettered in a time of great genre fluidity is cause for optimism.

Townes began her tenure on Columbia Nashville with spare acoustic recordings, and concluded it this year in similar fashion. She was, and remains, an ardently openhearted singer-songwriter, bent on tapping deep veins of empathy whether she’s in observational or confessional mode. When I first interviewed her, it made all the sense in the world to hear her say she felt a kinship to singer-songwriters like Patty Griffin and Lori McKenna. It also struck me that Townes’ singing – curling syllables and stretching out lines with feeling, a style sometimes called “cursive” singing – was far from the hearty enunciation for which country music has been known.

In between then and now, Townes dropped an album that bore a super-producer’s digitally sharpened touch, won a pair of ACM awards to go with the pile of honors she’s received from the Canadian Country Music Association – which began to recognize her promise when she was a teen with dreams of pursuing music beyond Grande Prairie, Alberta – and she toured with big country names like Miranda Lambert and Dierks Bentley. Townes also faced enough professional hurdles, and observed enough changes in the landscape around her, to reconsider where her songs might belong. And I very much wanted to hear about that.

Jewly Hight: You’re presently on tour in Canada, aren’t you?

Tenille Townes: I'm having the best time on this run. It feels like a community at these shows. We've done a few tours through Canada at this point, but this was our first time going as far east as we did. I feel like live music in general is a little bit more scarce over there. They don't get as many people making the trek. And so [I could feel] the appreciation.

They sold out the shows so fast and they're singing all the words. And very quietly listening intently and leaning in a really vulnerable way. And then also having a blast and being loud, which is so cool to me, for it to feel like a living room and a rock club at the same time. That's been such a big part of my vision.

I don't know how far out you planned this tour, but I wonder if it’s become an important chance for you to return to your home turf, regroup and get reinvigorated.

Yeah, it honestly feels really essential in my creative journey. I could not be more grateful for the way the timing has aligned this year for this moment on the road. It feels like the ingredient that I've been craving. In January, I'm going to be so ready to dive in with my whole heart and make [the music] I'm going to share next. I don't think that the recipe could have ever been complete without this tour in this moment. It feels so timely, because so much of this past year has felt terrifying.

And just standing on my own two feet as an artist again, pretty much entirely, I feel so excited and grateful to be making this leap into the arms of these people showing up at the shows who are so excited about this new chapter. And it's such a wave of encouragement to go, “Oh yeah, I think I'm on the right path, doing the right thing.”

How is it different from when you’ve toured the U.S., in terms of headlining versus being an opener, the size of venues and how you're engaging with the audience?

There's been a lot of theaters for us on this run, which have a bigger capacity than some of the clubs that we've played in these towns before. It's our first time playing a handful of these [places], but this is our third headlining tour in Canada.

What I noticed that's different is when it's our shows and our community, it just feels like people show up with open arms and they're requesting songs that I haven't played in so long. They know the deep cuts. They're showing up excited for a night of feeling whatever they need to feel. And I think that emotional permission feels different at our shows than it does at a show where we're a guest [in the opening slot] going to make some new friends. And it's been really cool hearing from people that were like, “I saw you on the Dierks [Bentley] tour and this is our third Tenille show.”

One thing I always say at the top of the shows is I want our time together around my songs to be a place where everyone who walks in the door feels safe to show up and be whoever they are and to feel embraced and welcomed for that. And I thank everyone for buying a ticket and for showing up as that community. And I really feel like they're embodying what that means.

Years back, I took note of the fact that Corb Lund had what was considered fairly mainstream country success in Canada, but he played Americana events when he came to Nashville. I’m curious whether you’ve seen folk, Americana and country are treated as separate genre categories in the Canadian market, like they are in the U.S. How do you tend to get categorized in Canada?

At least from my experience, it feels different to me. Because in Canada, I have been really grateful to have felt super embraced by the country community, by the CCMAs, by country radio, by the community of people listening to country music. And we have fit in that bubble there. And I don't know that we fit the same way in the States.

I relate to what you're saying about Corb Lund. I think maybe the lane is just not as narrow in Canada. And I think that they're just more in it for live music of any capacity. I think most fans [who come see me] would be like, “Oh, I'm at a country show.” Which is funny because when we play shows here, that doesn't necessarily feel the same. I do feel like the Canadian country music community definitely jumped on board with what I'm creating. And the music [I release in both markets] is very much the same, so it's so strange.

I will say that the people coming to our shows, our headline club shows that we've done in the U.S., they feel very similar, like-minded people to me.

You’re a little more than a decade into your Nashville tenure at this point. Why is it important to you to stay?

Even though this town has a lot of jagged edges or hard things about it, I really do still feel inspired here. I feel like there's a tapestry of artists who have come to this town with their dream and worked at sharing their art and building a group of friends and people around them who support that. I have a front row seat, you know, going to an Emmylou Harris fundraiser at City Winery and watching all of these people that she's embraced in her life that she's written with or jammed with that’s really a legacy.

I love this community, and I do feel inspired musically, having access to so many songwriters and musicians and producers. There is a heartbeat to this town that I want to continue to be present in and be a part of for sure.

I can picture the show that you were just describing. The atmosphere was very similar at the tribute to Mary Gauthier during AmericanaFest, a multi-generational gathering of Nashville’s singer-songwriter community

When we first talked all those years ago, you described being an astute student in Nashville, paying particular attention to singer-songwriters like Lori McKenna and Patty Griffin. At the time, you considered them touchstones because of how they used the language of the heart in their storytelling.

In terms of their career arcs, their material’s been recorded by big names in country, but as respected as they are among songwriting connoisseurs in that world, they've had contemporary folk careers as performers. They’ve often released their music on independent labels. Were you also taking note of what their professional paths have looked like? Or are you now?

I honestly don't know that I was conscious of it back then. It was just the music that I loved. I don't think I even had an understanding of the choices made on an artist’s path to stay true to that route.

I've learned a lot in the last handful of years: “Oh, that makes sense why a certain path, like Patty Griffin’s, unfolds in a certain way.” I never thought of it as a ceiling or an alternate route. It just was where the music had taken her. That's been inspiring to me.

I never want to look at any options of teams to work with or whatever with any closed-doors feelings. I would love to play the music that I make in stadiums. That'd be great if that still unfolds that way. But I also just really want to tell my stories and my truth, and whoever is going to come as the audience, that's amazing to me. The idea of seeing it as a wider horizon than maybe a stereotypical path, that doesn't seem scary to me. I think that's because I’ve looked up to people like Patty or Lori, people who have always stayed true to what they're doing and figured out the path there regardless. But I don't know if I've ever actually intentionally thought about it that way.

Your intention has been clearer than ever this year. It wasn't lost on me that the final two songs you released earlier this year, before you parted ways with your label – “As You Are” and “The Thing That Brought Me Here” – each were expressions of commitment to staying the course. What did you want to communicate?

I love that you noticed these themes. At the end of that journey, “As You Are” felt like such a great theme to end that season on. There was lots of resistance [from the label] in several years of working on music and getting to a point of actually getting to put it out. But that song always had a green light from them, which I really appreciated.

I wrote that song thinking it was about showing up and being a support system for someone. I had friends in mind that I was thinking of. It was just like, “I will be that safe place.” And then listening back to the demo after the [session] on the drive home, I was like, “No, I wrote this ‘cause this is what I want to hear when I'm struggling to let somebody in.” That's been something that I've felt even in my professional journey for sure, just wanting to feel seen.

It really seems like you’re the one communicating on your own TikTok. In recent months, a lot of your posts have been about celebrating your professionally “single” era. When you shared the news that you were no longer in your major label deal, you framed it as a breakup that you were happy about. What felt right about striking that tone?

It felt honest. It was a lot building up to that decision, and it was not easy, and it was terrifying. All of those emotions were a part of it. I just felt like, “I can't continue to share the music I want to make if I'm not letting people in on my process of that vulnerability, even when it's hard.” Making those videos felt scary, for sure. But that just feels like the kind of artist that I want to be, to walk the walk.

Also part of my intention was, “This is something that creatively feels really empowering to me, to take back the ownership of my music.” And for any young girls out there, I want them to know, “That's a possible feeling for you, to stand up for yourself at any moment in any kind of career, or on any path of your life.” It's brave to take that step. And I guess I just want that invitation to be there for anyone following along.

And I want to bring together the community of people. Like, it is an “independent artist,” but I think it should be called a “community village artist,” because you can't get your stuff out there without people believing in what you're doing and coming with you.

I wanted it to be very clear that we're in this together. We've always been in it together, but it feels very defined to me now. And I wanted to make sure everyone knew that.

And now we have the benefit of accumulated perspective, so I want to reflect back. At the beginning of your label journey, what was in the atmosphere at the time in Nashville or the country music scene in the U.S. that contributed to a sense of possibility for you?

At the beginning, it was excitement. And [I] look back and think, “How crazy cool that I got to be a part of a major label deal that let me put out a debut single about homelessness, and then follow it up with a song called ‘Jersey on a Wall’ about losing someone in a car accident?” I'm so glad they gave me a chance to put out songs that were different and that sonically didn't sound like a sure bet. I will always appreciate that. And it set me up with so many people who heard this record and the songs because of the way that they helped lift it up.

So I have nothing but love for that season. It might not have hit the thing over all of the world's fences by any measure of what you measure as success. But to me, it's a win to think that I got to share that art and that people found it and that they get to keep finding it because of that.

Years back, you told me that in one of your initial meetings, when you played some songs in a boardroom, the head of the label compared you with Jeff Buckley, which was a funny thing. In hindsight, I think that kind of speaks to the fact that you were bringing a sensibility as a singer-songwriter that might've been a little bit outside of their frame of reference.

And maybe the Jeff Buckley comparison – as much of a stretch as it was – was a gesture of someone who lacked the frame of reference or language for what they were hearing. Because the way you elongate your vocal phrases and hold onto lines is more akin to the “cursive” singing style that’s been a thing in indie music, folk, pop and R&B than in country, with its crisp enunciation. What kinds of conversations did you have about what you were doing, how they heard it and how they thought it fit into that world?

It is really fun to reflect on that. I definitely think from that initial meeting, they were going, “This is something that doesn't necessarily fit in what that normal trajectory would be.”

I think that has been the compass that's directed it a little bit left of where things would traditionally fit coming out of the system that they're used to. I think they knew that all along. And at moments, that definitely made things a little bit bumpier or harder, because it wasn't something that naturally made all the sense in the world, I don't think. And I'm totally great with that.

I revisited the body of work that you released on the label, and I didn’t hear you bending your songwriting approach, singing style or artistic identity to any kind of mold that was really popular in country music at the time. What did it take to maintain that?

There was never an intention of, “Okay, that's mainstream, so I'm closing the door to that.” I've always felt very open-hearted in the writing room. It's just what was coming out of what I was making that I loved the most. The Lemonade Stand came out in 2020. Then I wrote the songs for Masquerades all on Zoom in my house by myself. It was a time when I didn't feel as much outside influence of commerciality. I was just honestly writing to express something and feel better.

We certainly, production-wise, had moments of trying to be strategic about what kind of things might — I don't know — reach more people or something, or sonically be something that could be more mainstream. So there wasn't a lack of strategy in that. I just had to follow the songs, I think.

On TikTok, you’ve shared clips of songs that you've had in the can for years that you said the label didn’t want to release. How did the disagreements over your artistic direction begin to emerge? And what was at stake for you when they did?

I think the biggest rub maybe was being able to plan far enough down an artistic vision, because it was just like, “We'll see how this one does.” And the targets just kept moving. Mentioning putting out an EP or a record was scary. They were like, “No, we can't. We gotta just take it one step at a time.” So I think that became the hardest thing, and where a lot of songs fell through the cracks, because we didn't hit certain measures to be able to go to the next. We still found ways to push through and get music out. It just didn't happen in a guaranteed, planned-out manner, necessarily.

What brought you to the place where you were ready to part ways?

I could feel it building for a while, for sure. And when it came to the point of putting out “As You Are,” there was a group of songs that were ready, and we were just getting resistance on putting out more than one or two out again. And honestly, they came to us and [said], “I don't think we can put out the rest of these.” And it was like, “Okay, I think it's time to go.” It wasn't like I'd arrived at this place of courage. Circumstances were like, “Okay, I think the arrows are really pointing that this is the moment to take the leap, and I'm just going to do it.”

What did you see yourself as leaving behind and moving towards instead?

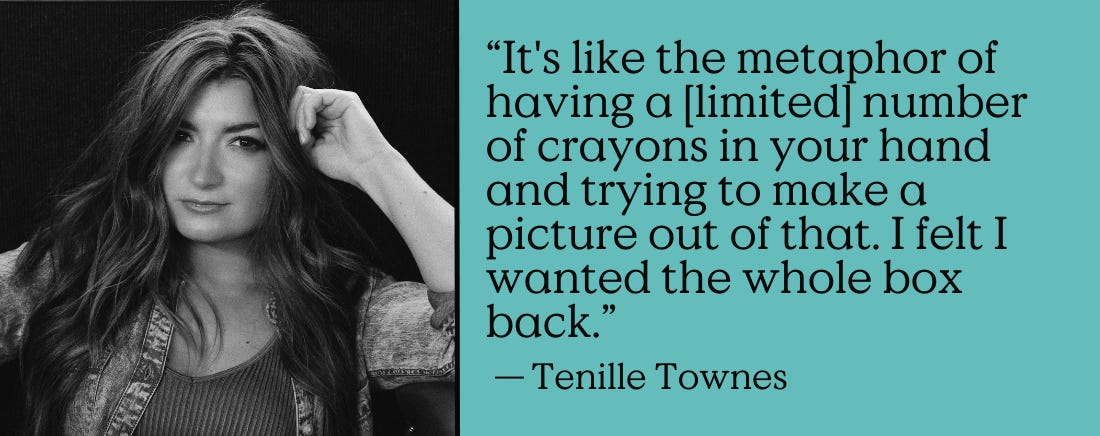

The idea of taking back ownership of what I create and jumping into this place of freedom in the sense of less hoops to get through to actually get songs to people. I think creatively, I needed change as well.

I'm so proud of that whole journey. I have no regrets, but in a lot of ways, it's like the metaphor of having a [limited] number of crayons in your hand and trying to make a picture out of that. I felt I wanted the whole box back. I never felt like I was trying to create something to fit within [the industry], but I do feel like that kind of a system can't not have an effect on what you're doing creatively.

I feel this freedom in my hands. What do you do? That's a whole other process that I'm in the middle of right now, trying to figure out exactly what I want to say and how I want to sound next. It's so liberating, and it's also just, “Oh, this is up to me now.”

When you look back on it, do you think that label partnership was no longer the right fit for you, or that the mainstream country marketplace that it exists in was not the right fit for you?

I don't know. I think maybe a little bit of both. But mostly, I think the major label system just ran its course for me. And I feel open to whatever team there may or may not be in the future. I wouldn't write that experience off ever again. I think it just depends on the season I'm in creatively and what people are behind it.

What's funny to me is looking back on the history of country music, the things that have [at certain moments] laid on the outside have actually [become] pillars of what's created the format that we love and know. So it doesn't scare me to [say], “I don't actually feel like I belong in what we call right now the mainstream of country music.” I'm just going to do my thing and whatever we want to call it later, looking back, it's fine with me.

Earlier we were talking about the singer-songwriter ecosystem that’s long existed in Nashville and has amorphous boundaries – those songwriters play their own intimate shows and write for bigger names in other lanes.

But there’s been far more visible crossing of boundaries than that this year. We've had pop superstars going country, and Kacey Musgraves – who never fully left her country label, but was viewed as drifting towards pop – made a folk-pop album that’s gotten her country awards nominations again. And then there are artists like Noah Kahan. I know you've expressed admiration for what he does. He's been having great success with songs that are grounded in folk, but he exists in the pop world – and yet he’s also gotten Americana and country nominations. Have you been looking around you and taking note of how other artists are transcending genre boundaries?

Yes, and it feels so encouraging to be like, “How about you just make what's you?” And then, what if there are different categories of music lovers who want to listen to stories and songs and voices and actually don't care what sticker you put on it?

[As for] Noah, that's just songs that are speaking to people at such a loud volume. I don't know what you call it, and it doesn't matter. Longterm-wise, I think Brandi Carlile’s path is a flashlight, to have something that's just evolved with her as an artist and fit in so many different places. And I think about Patty Griffin. Even somebody like Billy Strings, Marcus King, I think is incredibly inspiring looking at all of these people who are not sticking to one lane.

You are actively narrating the decision-making process for your audience and frequently discussing what it looks like to be an independent artist, what that means, what your aims are, what challenges you face. From what I've read, you’ve kept some important parts of your team, management and publishing, but other aspects of the model have changed. What do you feel are the most significant differences in how you're operating at the moment? What do you most want people to know about your present reality?

I think the biggest shift is how much making videos is a part of actually getting a song to be heard at all. And the creative output of just trying to make noise in a place that's got way too much noise going on, the internet. That's the most overwhelming thing that’s very different than what I thought it meant to be a singer-songwriter and write songs and tour.

I'm trying to balance the creative output of constantly being like, “Hey, I'm over here. This is what I'm working on.” And also making sure that my soul is in a good place, not just spinning on a hamster wheel, so that I can make something that I'm really proud to stand on in my life.

I’ve heard that you are working on new music. Are you broadening your circle of collaborators?

Yeah, definitely. I've been reaching out to people I've not written with before, people I'm just fans of their music and [asking], “Hey, let's write or let's get together and just jam.” And then I'm in the stage [where] I'm always writing. I'm at a point where I have a lot of songs and I'm trying to just zoom out and go, “Which ones are speaking the loudest to me?” The theme for me right now is very much about betting on yourself and getting to the heart of the matter without everything feeling too heavy and serious.

I'm at the spot of taking song inventory and trying to make some new friends and keep writing, and working on what might be next.

Won't it be wild if you have an album that is on a Canadian country chart and then in the U.S., is on Americana and folk charts, the same collection of songs?

I think it's possible. I believe it is. I love you putting that out there. I'm declaring it right now.

The expression of music is going to fit differently in different places. And I think that's more possible in the landscape we're in now than it ever has been.

Lead Image: Tenille Townes by Robert Chavers.