Editor’s Note: Read our exclusive interview with Marlon Williams on his new album, Te Whare Tīwekaweka, here, then dive deeper into the project, its inspirations, and foundations below.

When it comes to making his art, the Māori New Zealand singer-songwriter, performer, and actor Marlon Williams draws on an expansive family tree of influences cribbed from the rich histories of folk, country, bluegrass and popular music in North America, Australia, and at home in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu (the North and South Islands of New Zealand).

However, as his stunning new album Te Whare Tīwekaweka (The Messy House) – sung entirely in his indigenous tongue, te reo Māori – reveals, in the past, Williams has only shown us the tip of the iceberg of his creativity. During the process of creating this album, his guiding light was a traditional Māori whakatauki (proverb), “Ko te reo Māori, he matapihi ki te ao Māori,” which translates into ‘The Māori language is a window to the Māori world.’

Supported by lush, throwback country & western slanted arrangements and instrumentation, his te reo Māori songcraft offers a captivating doorway for those willing to pass through it.

Recently, Williams spoke with Good Country for a Q&A interview, which you can read here. To help unpack the depths that underscore what he’s accomplished here, we’ve assembled this supplementary article to help readers dive deeper into his world.

Just a twenty-minute drive from Ōtautahi/Christchurch, Ōhinehou/Lyttelton is a historic, hillside port town that looms large in Marlon Williams’s story. In an article for North & South magazine’s May 2023 issue, writer George Driver noted, “Lyttelton has a population of 3000, but probably has more award-winning musicians per capita than anywhere in the country.”

Since the 1970s, Lyttelton has cultivated a resourceful arts community drawn in by cheap housing and the dramatic landscape. Two and a half decades into the 21st century, it’s more explicitly associated with a wave of wandering New Zealand alt-country, folk, and rock musicians, including Lindon Puffin, The Eastern, Delaney Davidson, Aldous Harding, and our man of the moment, Marlon Williams. In Williams' words, “I feel very lucky in the way that the town and the culture it has fostered keeps pushing me forward.”

As the music historian Chris Bourke observed in his excellent overview of the history of folk, country and blues in New Zealand for Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, “New Zealand folk music originated [in the 1790s] with sealers, whalers, gum diggers and bushmen who sang while they worked or for after-hours entertainment.” By the mid-19th century, Māori composers began adapting European melodies into songs penned in te reo Māori, laying a process of cross-cultural musical fusion that continues to this day with Te Whare Tīwekaweka.

American country music, however, arrived in New Zealand in the 1920s and was quickly adopted by local country linesmen like Nelson’s Tex Morton, an accomplished songwriter, yodeller, hypnotist, and sharpshooter who went on to have a career in Australia and America. Soon enough, a new generation of New Zealand country singers like Jack Riggir and the Māori cowboy Johnny Cooper were finding fledgling success as recording and performing artists.

To get a fuller sense of how folk and country music developed in New Zealand, check out Bourke’s Folk, country and blues music history here.

Marlon’s co-writer on Te Whare Tīwekaweka is KOMMI (Kāi Tahu, Te-Āti-Awa), a Lyttelton-based vocalist who performs in the regional dialect of Kāi Tahu – the principal Māori iwi (tribe) of Te Waipounamu (the South Island of New Zealand). Outside of music, they are a writer, poet, activist and university lecturer.

In recent years, KOMMI has helped Williams refine and hone his lyric writing in te reo Māori. Grounded in Māori spirituality and concepts like Mākutu (witchcraft) and Tūrehu (faeries), they describe their music – a melange of hip-hop, dub, gothic rock, and electronica – as Witch-Hop.

Listen to a Radio New Zealand interview with KOMMI here. Watch Marlon and KOMMI discuss Te Whare Tīwekaweka on In The Pits here.

Broadly speaking, Williams understands himself as coming from a few different established musical traditions: choral music, operatic music, bluegrass, and folkloric Māori music. You could also make the argument that his music has something in common with the lounge music sensibilities associated with a generation of mid-to-late twentieth-century Māori pop singers like John Rowles, Prince Tui Teka, Howard Morrison, and Dalvanius Prime, many of whom emerged out of the Māori showband era.

“I think I’m part of a tradition of tradition-melders who gather whatever is around them and find a way to make something new with it,” he said.

To learn more about the Māori showband era, read Leonie Hayden’s excellent 2019 article for The Spinoff, Kaupapa on the Couch: the incredible Māori showbands.

In his lifetime, Dr. Hirini Melbourne (Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Kahungunu) played a central role in the revitalization of the indigenous te reo Māori language via spare and straightforward but unforgettable folk songs collected in his children's songbook Toiapiapi (1991).

As part of a generation who grew up learning and singing Melbourne’s songs in their primary school classrooms, Williams cites him as helping to provide the foundations that would later allow him to record Te Whare Tīwekaweka. Alongside his language efforts, Melbourne worked with Dr. Richard Nunns to bring Taonga pūoro (traditional Māori instruments) back into the lexicon of experimental and popular music in Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Learn more about Melbourne in this Te Whare Taonga Puoro o Aotearoa | NZ Music Hall of Fame article here.

Filmed over four years by the director Ursula Grace Williams, Marlon Williams: Ngā Ao E Rua – Two Worlds is a forthcoming documentary that follows Marlon through the creation of Te Whare Tīwekaweka and all the trials, tribulations, and moments of transcendent beauty that came with recording his first album in te reo Māori.

As Williams noted in our interview, “I thought, ‘Right, they’re filming me, so I better do what I’m saying.’ Part of the intentionality was that the documentary would frame it into a real thing and make it happen. There was nowhere to hide.”

In May, Ngā Ao E Rua – Two Worlds will arrive in New Zealand cinemas with Australian and North American screenings set to follow. More info here.

Born in the coastal North Island city of Tauranga, Mark “Merk” Perkins is a New Zealand singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer who made his name releasing psychedelic bedroom pop records in the late 2010s. Outside of his own music, Perkins has worked as a co-writer, session musician, producer and engineer for a range of New Zealand artists, including Delaney Davidson, Adam Hattaway, Lisa Crawley, Soft Plastics and Williams.

Perkins and Williams first crossed paths while playing at the same show in the late 2010s. Since then, they’ve worked together on a film soundtrack (Juniper, 2021) and William’s last two albums, My Boy and Te Whare Tīwekaweka. “I fell in love with his musical and emotional sensibilities,” Williams said. “He’s just a great person to do pre-production with and work out the nuts and bolts of a musical world.”

Listen to Perkins' most recent album as Merk here.

Named after The Yarra Hotel, a legendary pub venue located in the Australian arts and culture hub of Melbourne, Ben Woolley (bass), Gus Agars (drums) and Dave Khan (guitar, fiddle, etc.) – AKA The Yarra Benders – are Williams' longtime backing band. Outside of The Yarra Benders, Woolley, Agars, and Khan work as session musicians with a who’s who of New Zealand and Australian folk, alt-country, and alt-rock acts. Khan is also known for his work as a record producer, helping to craft albums by the New Zealand singer-songwriters Tom Cunliffe and Reb Fountain.

Although none of the three are fluent in te reo Māori, Williams saw them as the perfect players to support him while recording Te Whare Tīwekaweka. As he put it, “It was just a little stumbling block and a gate people had to go through. They had to be humble with not having full knowledge of where we were going. It just made them listen more and feel things more acutely.”

The He Waka Kōtuia Singers are a kapa haka roopu (Māori performing arts group) from Ōtepoti/Dunedin in lower Te Waipounamu. They perform traditional and contemporary songs and haka that tell the stories of their connection to the land, celebrate their ancestors’ deeds, and promote indigenous values for future generations.

As they explain in their Instagram bio, “Kapa Haka (group dance) is the vehicle through which our members learn Te Reo, Tikaka (customary practices) and re-connect to the Taiao (the natural world).” In 2019, the group recorded an album called Te Mahi Tamariki with guidance from the celebrated Māori psychedelic soul musicians Mara TK and Troy Kingi. Several years on, Williams brought them on board to contribute to Te Whare Tīwekaweka.

Listen to The He Waka Kōtuia Singers Te Mahi Tamariki album here.

In our interview for Good Country, Williams touched on an important point about how walking between worlds, cultures, genres and countries in music and life relates to his Māori heritage. In his words, “A lot of the celebration around this record is the celebrating the ability of Indigenous people – in this case, Māori specifically – to absorb what is going on in the world and make something from it.”

When I asked Williams how he felt spending a decade recording and performing music worldwide has shaped his life, he offered up some lucid thoughts. “I feel like a merchant,” he said. “I’ve become somewhat worldly. I have so much faith in my natural musical and thematic proclivities that I don’t feel closed off. The more I see the world, the more I feel open to letting it influence me. That’s been the nice thing about touring. It really universalizes your sense of what’s possible, who you are, and what you can be.”

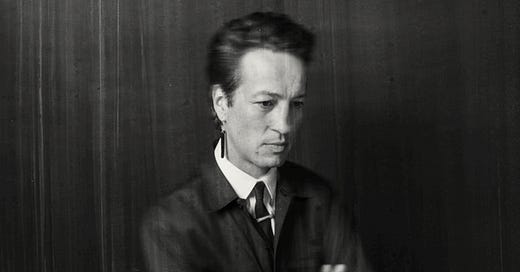

Lead Image: Marlon Williams by Steven Marr.

This is absolutely amazing, thank you so much for this. Can’t wait to sit down and properly follow up these links and leads.